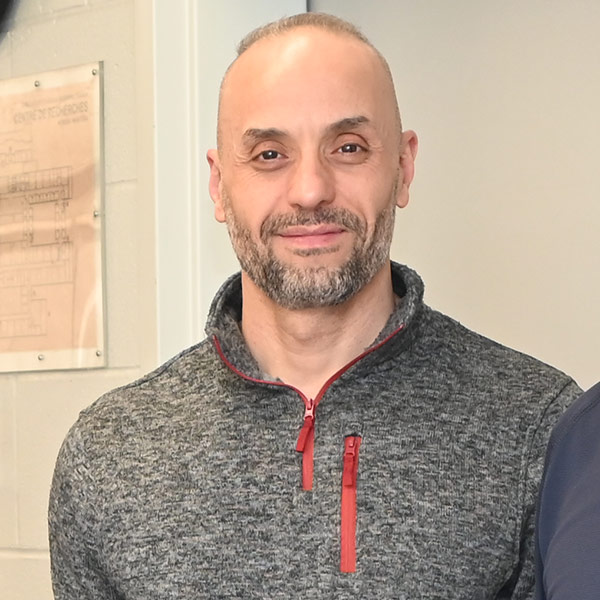

Afua Mante, assistant professor, University of Manitoba

Afua Mante is an assistant professor of soil physical processes in the Department of Soil Science at the University of Manitoba (UM). She was born and raised in Ghana, where she attained a bachelor’s degree in agricultural engineering and a master’s in water supply and environmental sanitation. In 2011, she moved to Canada as a graduate student at the UM, where she completed an additional master’s degree in mechanical engineering and a PhD in biosystems engineering.

Where did you work before your current role at the UM?

I worked at the Centre for Engineering Professional Practice and Engineering Education in the Price Faculty of Engineering at the UM as a post-doctoral fellow for two years (2018 to 2020) immediately after completing my PhD program. In that role, I was responsible for identifying, through consultation and collaboration with stakeholders, meaningful ways for genuine inclusion of Indigenous knowledges, perspectives and design principles, as well as principles of sustainable development and sustainable design, in engineering curricula. After that, I joined the land remediation group in the Department of Soil Science as a post-doctoral fellow, where I oversaw projects on the restoration of prime agricultural lands disturbed by industrial activities. I stayed in this role until January 2022 and then stepped into my current role in the same department as an assistant professor.

What got you interested in this area of work?

It all started when my uncle made what I had seen in junior high agricultural science textbooks become a reality. Use of agricultural machinery was a dream in my community. My uncle got a small tractor with one plow and one harrow. This set of machinery was “gold.” You could see the pride in my uncle’s face. You can bet he used all his savings on them. No financing opportunities. All he wanted was for the crops to meet the rains at the right time. This investment paid off. He saw an exponential increase in yield – his team was so proud to work with him and it provided my family with security.

More than that, I got the opportunity to see the equipment in action. I was mesmerized watching the whole show. My uncle said to me, with a smile on his face, “we have people who research into how these machines work.” That got me interested in pursuing the agriculture path.

I received opposition to that idea from some of my high school teachers. They had not experienced the magic of agriculture, or they were somewhat disconnected from how we need agriculture. To them and many, agriculture was a way to punish kids at school. It had a negative image. I was lucky to have experienced my uncle’s investment at work. My decision was solidified when I figured out that one of my mentors who had visited my high school to support our education was pursuing agricultural engineering (which I did not know existed at the time) at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. He enlightened me on career opportunities in agriculture and from then on, I never looked back.

Tell us a bit about what you are working on at the UM.

I teach the course “Soils and Landscapes in our Environment” at the undergraduate level, soil physics courses at the undergraduate and graduate levels, and the equity, diversity, inclusion and bias sections of the “Principles of Scientific Research and Communication” course at the graduate level.

I run the soil physics research program. In the program, I supervise both graduate and undergraduate students on various projects. We collaborate with stakeholders to identify opportunities and address challenges to advance the agriculture industry. With our projects, our main goal is to understand the complexity of the soil system and how to subject it to applications and interventions in a sustainable way to allow us to continue to enjoy the ecosystem services it lends to us. Currently, we are looking into a wide range of applications and interventions, including farm traffic systems, extreme moisture events, cropping systems, nutrient management, freezing and thawing processes, brine contamination, pipeline construction, and how they interact with the soil for sustainable crop production and a healthy environment. There is more room to expand our research, considering the complexity of the soil system.

I am currently collaborating with two researchers at the UM on a project, “Building resilient soils with cover crops in Manitoba,” funded through Manitoba Crop Alliance and the Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership (Sustainable CAP). In recent years, we are seeing an increase in the number of farmers in Manitoba who are adopting cover crops to conserve the soil, for nutrient cycling or for improving soil health. In addition to these benefits that are associated with cover crops, we are exploring how cover crops can improve soil strength to support trafficability and reduce the risk of soil compaction and other soil deformation processes. Our focus is not just on the wet condition, but also on the dry condition, as that contributes to the deformation processes of the soil under our climate. This project is an opportunity to present a holistic view on the benefits of cover crops integrated into annual cropping systems by taking into account the agronomic and climatic conditions that prevail in Manitoba.

What can you say about the value of farmers providing funding and support to your organization?

As we know, producing food has many pieces to it. In our province, our climate and our wide range of soils make our challenges unique. To overcome these challenges in our community, we have to recognize that we all have a role to play. But here is the catch: it is one thing knowing you have a role to play and quite another having the resources to support your role.

Farmers’ financial contributions to our research programs make it possible for us as researchers to play our role. We are able to train highly qualified personnel (HQP) for the sector and secure resources we need to address current and emerging challenges in our community. This ongoing farmer support demonstrates a community where we all work together for continued success.

How does that farmer funding and support directly benefit farmers?

As I mentioned earlier, there are several pieces to producing food. When farmers provide the support, they set the priorities. They directly influence the sector. They tell us what their actual challenges are. Many times, what we may perceive as a problem is not seen as such by farmers. Also, how we may define a problem to provide solutions may not align with the reality of management. As key stakeholders, we consult and collaborate with them to create working solutions. Knowledge sharing through the life of a research project and after becomes integral to the research. It promotes accountability as well as (re)evaluation of the outcome. Also, with the plethora of challenges the community faces, we need all hands on deck. When we train HQP, we build the workforce needed to tackle the challenges. All these lead to fostering stronger relationships in the community.

Anything you want to add or any comments to our farmer members?

Farmers are our heroes. It is my hope that we all recognize that. They begin the story of the food on our plates. It is a very lengthy story. We may not always hear the story, but what we can all agree on is the excitement and the sense of renewal we have after treating ourselves to a wonderful meal. Thank you, farmers.

How do you spend your time outside of work?

I serve as the vice-chair of the Canadian Foodgrains Bank board of directors, where I offer my perspectives and leadership on the organization’s mission to end global hunger and shape Canada’s contribution to international aid and development. I also write songs and poems, which is a great outlet for me. The most fun thing I do is when my kids and I make up songs and sing them unending.

What is your favourite TV series right now?

Monk – a series on Netflix. The characters all have their unique strengths that they bring to accurately solving cases. What I have learned is that sometimes the strength of another may be frustrating when we are not used to it. It may be too slow or too detailed for us, and we think it could be easier to quickly jump ahead, but then it doesn’t lead us anywhere. When we begin to create the space to understand one another, we realize that we complement each other. To have an effective collective, we need to understand and accept the individuals within the collective.

What is the best part of your job?

The training of HQP. I have HQP from diverse disciplines. This requires me to be intentional about knowing them as individuals so that I can train the whole person. This leads to my HQP owning their training and accepting the challenge to be more. It is a joy to see such a development in them.