Managing Bt Resistant European Corn Borer

European corn borer (ECB) has long been a pest of Manitoba corn crops, but it is not only a nuisance to corn – crops like potatoes and hemp are affected as well. The larval stages of the insect are most economically significant due to their tunneling (boring) capabilities which disrupt the flow of nutrients and water, and the integrity of the stalk. Yields can certainly be affected by ECB presence, around 3-5% yield decrease being possible in standard incidences (5-9 bu/acre in a 175 bushel crop) and increasing in more significant infestations.

Until Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) traits were introduced to corn in Canada and the United States in 1996, corn farmers would rely on cultural practices and insecticidal control when economic thresholds were met. Cultural practices include crop rotation, residue management – destroying stalks where larvae overwinter successfully, and tillage that buries residue deep enough that larvae cannot survive. Insecticidal control is difficult due to timing between egg hatch and the boring phase. Diligent scouting to monitor egg hatch progress is extremely important to time when most eggs have hatched and larvae have not begun entering the stalk tissue yet. Once larvae reach the 3rd instar stage (7-10 days following hatch), they begin to bore into the stalk, and rarely resurface, rendering insecticide applications ineffective.

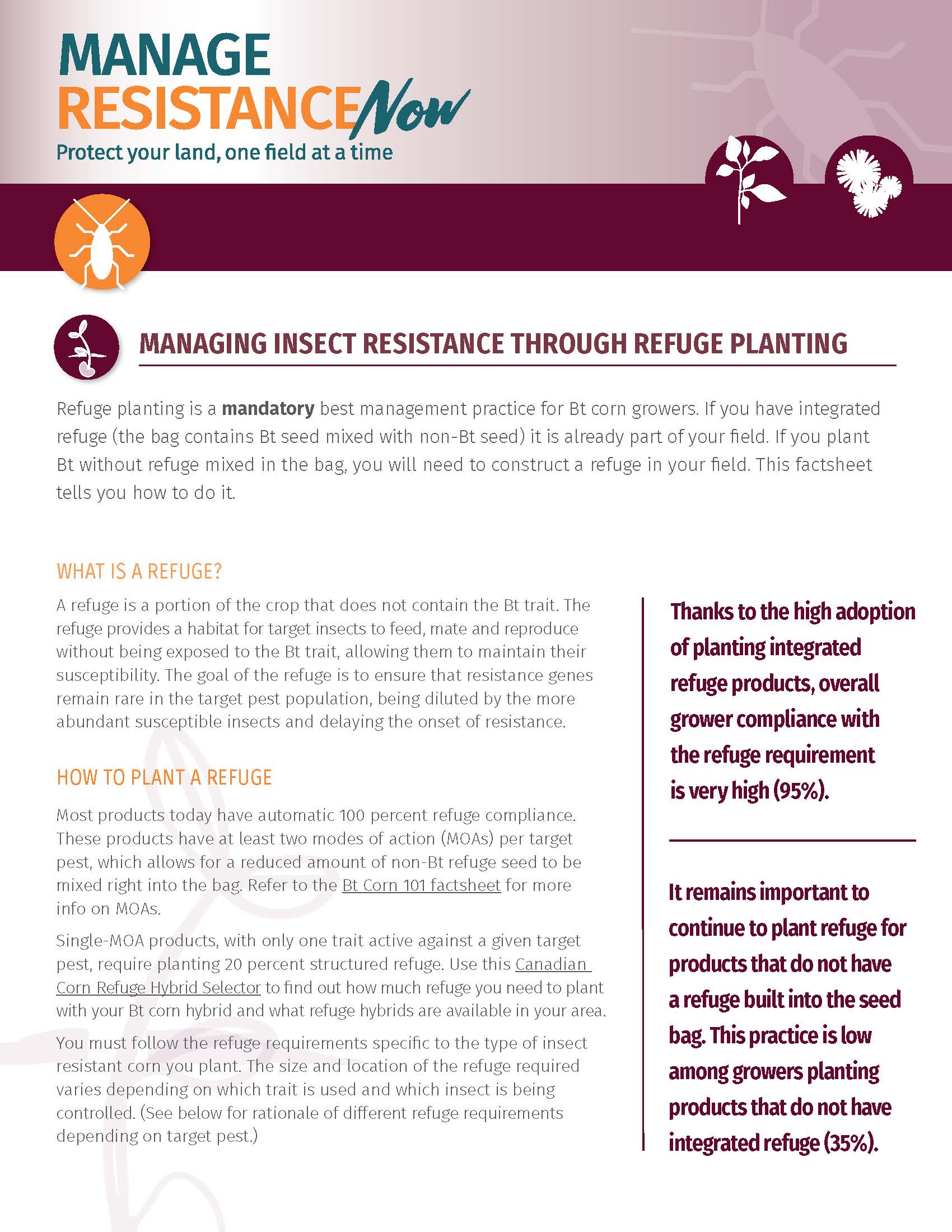

The introduction of Bt hybrids allowed farmers to not rely so heavily on residue management and insecticide application. Farmers were able to choose a fitting Bt-traited hybrid for their farm and had to match that hybrid with a refuge, or non-Bt, hybrid in 20% (or more) of the field in a block, strip or perimeter method. In more recent years, seed companies have come out with a 5% refuge system, called refuge-in-a-bag, making the system a lot easier for farmers to adhere to.

Unfortunately, non-compliance with pesticide requirements weakens the system and creates an opening for resistance. While the Bt trait is very strong, there is a small portion of the ECB population that are naturally resistant to the trait that controls the rest of the population. If farmers were to plant 100% Bt hybrids, those resistant populations would thrive and reproduce, eventually being the only population remaining.

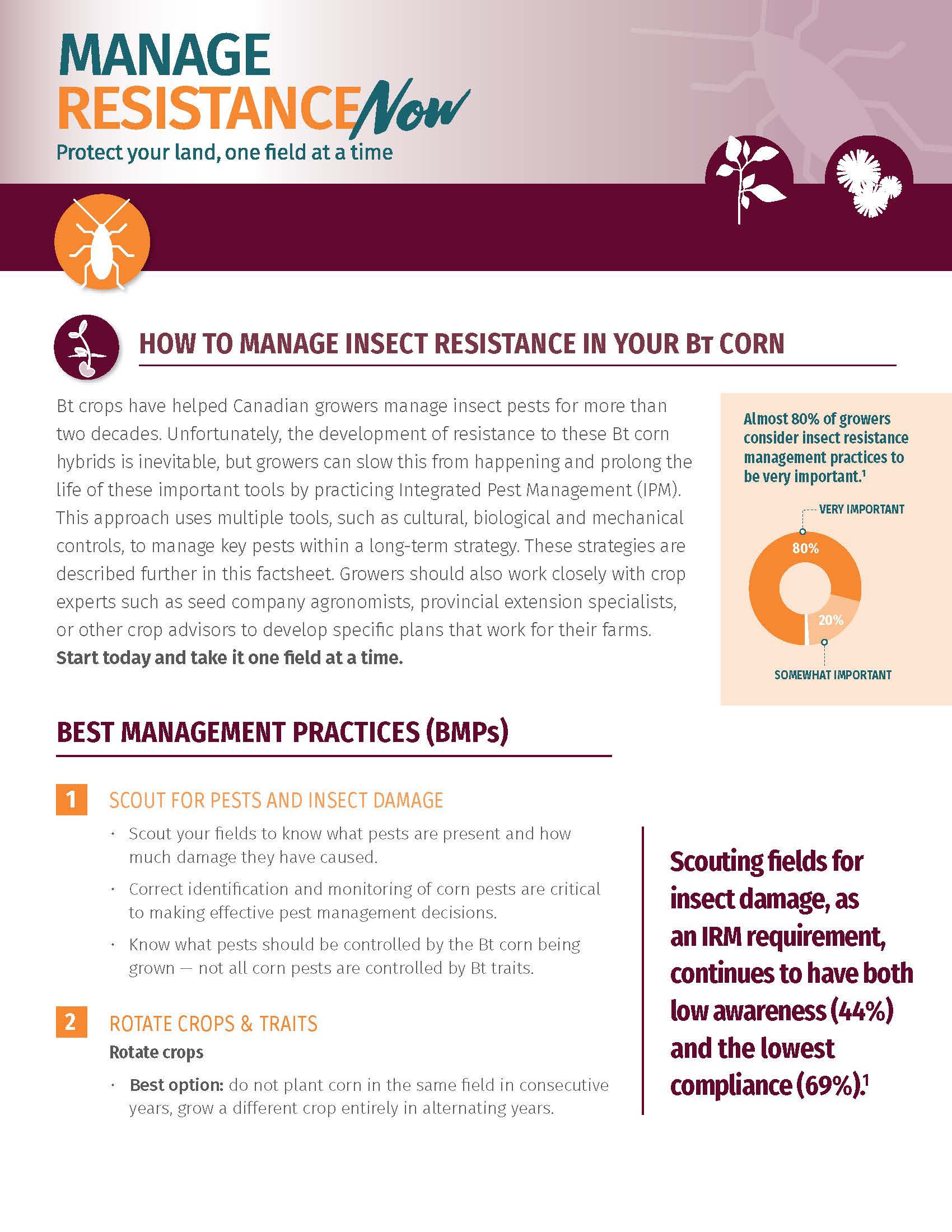

Managing resistance on-farm can feel daunting, but it is very straightforward. Best management practices to avoid European corn borer resistance to Bt traits include:

- Scout for pests and damage

- Rotate crops and traits

- Plant a refuge

- Manage with insecticides

- Keep accurate records

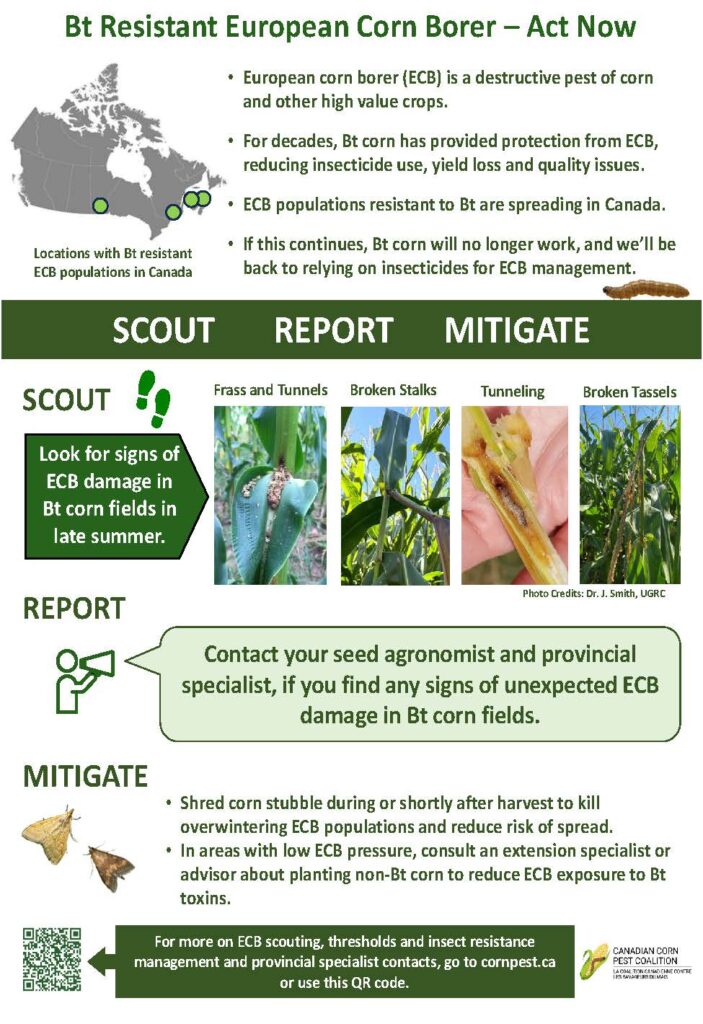

If there is a suspected case of ECB resistance in a Bt corn field, the following should be monitored to identify the issue:

- Scout – both Bt and non-Bt corn for damage

- Field Investigation – verify trait(s) present, evaluate presence and damage caused by ECB, rule out external reasons for damage

- Contact Seed Company – seed company representative must be informed if ECB damage is found in Bt-traited crop, where it is determined the pest is resistant

- Best Management Practices

- Collect Insects – the seed company will likely arrange for live ECB samples to be taken from affected field(s)

- Resistance Mitigation – if resistance is confirmed, farmer will be notified of next steps (see Managing Resistance in your Bt Corn)

Resources have been developed to help farmers, agronomists and seed companies identify issues in Bt corn fields as resistance incidents have occurred in Canada. Canadian Corn Pest Coalition is a group of industry members that work to develop extension and support to Canadian farmers and industry as insect issues arise. The CCPC has extensive resources available on their website on this specific topic, as well as other insect pests in corn. It is important for members of the corn industry to be educated on pest pressures that could turn into serious resistance incidents. Together we can improve the longevity of Bt traits so farmers can continue to use them safely and effectively.

Contact your provincial Extension Entomologist (John Gavloski, Manitoba Agriculture) or MCA’s Agronomy Extension Specialist – Special Crops (Morgan Cott) for further information on European corn borer resistance, what to do to avoid it, and how to determine if you see possible resistance.