Winter Wheat Variety Yield and Market Share Data – 2024

Manitoba Crop Variety Evaluation Trial Data

Winter wheat yield data from the Manitoba Crop Variety Evaluation Trials (MCVET) is in for the 2024 growing season. This data provides farmers with unbiased information regarding regional variety performance, allowing for variety comparison. Data was derived from small plot replicated trails from locations across Manitoba. Fungicides were not applied to these plots; thus, true genetic potential can be evaluated. Although considerable amounts of data are collected from MCVET, the disease ratings are from variety registration data.

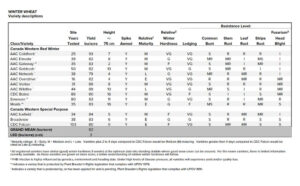

Table 1. 2024 MCVET winter wheat variety descriptions

Note: Table 1 sourced from MCVET team.

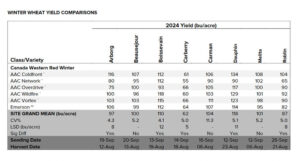

Table 2 below summarizes the yield results from the 2024 MCVET data by trial location. The yield results represent 2024 data only, therefore long-term trends should be considered when making variety selection decisions. Previous yield data can be found in past editions of Seed Manitoba. As well, apart from yield, there are other variety characteristics to consider when making variety selection decisions, such as disease, insect and lodging resistance. Check out this Manitoba Crop Alliance article for more information on considerations when selecting a new cereal variety.

Table 2 also indicates if there were yield differences between varieties at each trial site. If there was a significant yield difference the least significant difference (LSD) is also included. The LSD signifies the smallest difference necessary in bushels per acre for two varieties to be considered significantly different from each other.

Table 2. 2024 MCVET winter wheat yield comparison data

Note: Table 2 sourced from MCVET team.

MASC Variety Market Share Data

The Manitoba Agricultural Services Corporation (MASC) has also released its 2024 Variety Market Share Report. This report breaks down the number of acres seeded to each crop type in Manitoba, as well as the relative percentage of acres each variety was seeded on within each crop type. This information is useful to understand overall production patterns in Manitoba. A link to the 2024 report can be found here.

It is important to note that farmer members’ dollars directly contributed to the plant breeding research activities that were instrumental in the development of the top winter wheat varieties.

Select takeaways

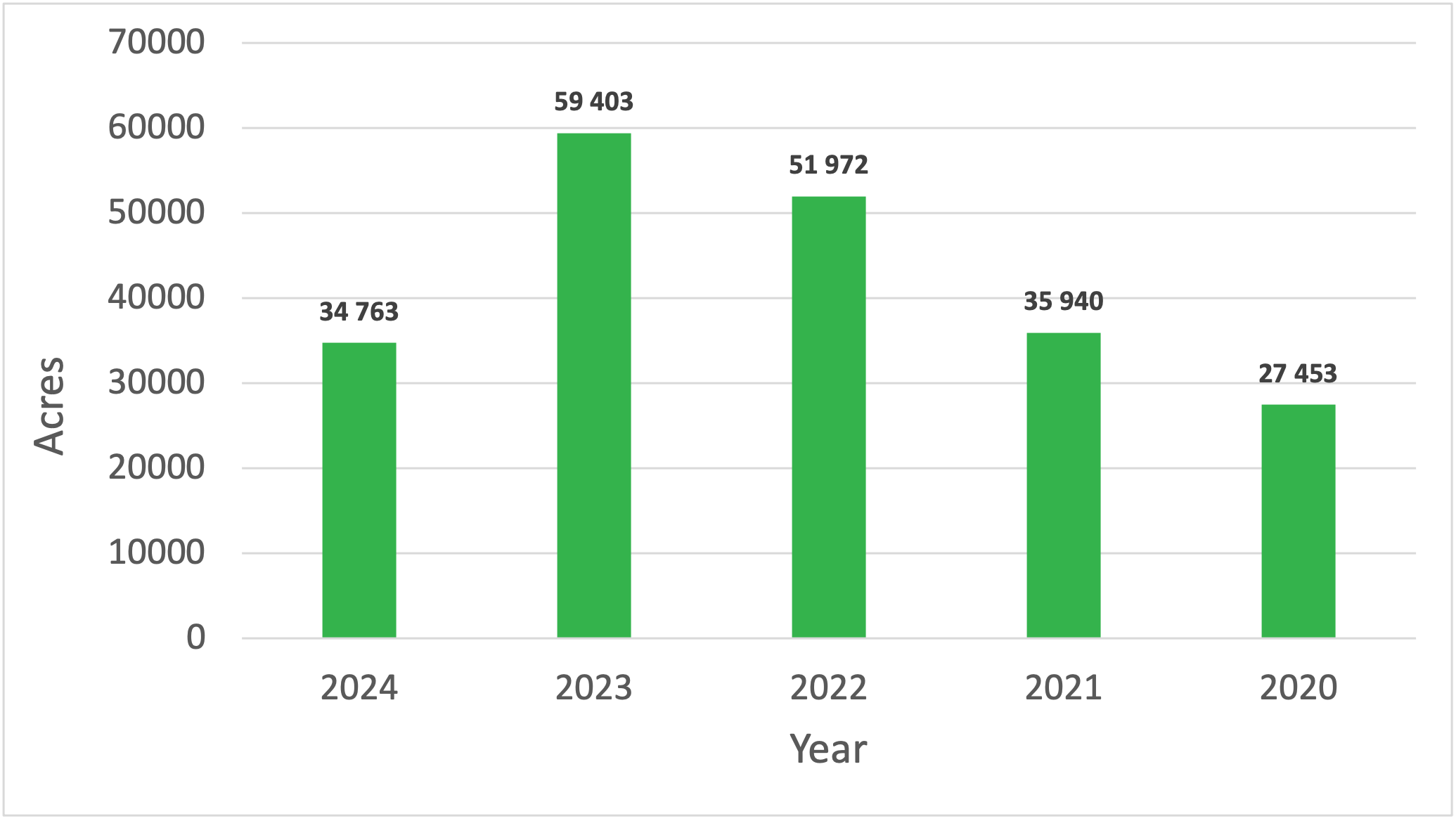

A small number of winter wheat acres were seeded again in 2024, with approximately 35,000 acres seeded.

Figure 1. Summary of the amount of winter wheat acres seeded in Manitoba over the last five growing seasons. Data obtained from MASC Variety Market Share Reports from 2020-2024.

Eight varieties by percentage acres seeded are listed in Table 1, these are the only varieties listed in this year’s MASC Variety Market Share Report. All eight seeded varieties are Canada Western Red Winter (CWRW) wheat.

Table 1. The top eight 2024 winter wheat varieties by percentage of seeded acres in Manitoba.

|

Variety |

Wheat Class |

Yield (bu/ac)** |

Relative Maturity** |

Lodging** |

Relative Winter Hardiness** |

FHB Resistance** |

Relative Acreage (%)* |

|

AAC Wildfire |

CWRW |

89 |

Late |

Good |

Very Good |

Moderately Resistant

|

52.8 |

|

Emerson |

CWRW |

83 |

Medium |

Very Good

|

Good |

Resistant |

14.7 |

|

AAC Vortex

|

CWRW |

87 |

Medium |

Very Good |

Very Good |

Moderately Resistant |

8.9 |

|

AAC Goldrush

|

CWRW |

82 |

Medium |

Good |

Very Good |

Intermediate |

7.9 |

|

No Var

|

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

7.7 |

|

AAC Gateway

|

CWRW |

82 |

Medium |

Very Good |

Fair |

Intermediate |

5.2 |

|

CDC Buteo

|

CWRW |

80 |

Medium |

Fair |

Very Good |

Moderately Resistant |

2.7 |

|

AAC Overdrive |

CWRW |

82 |

Early |

Very Good |

Very Good |

Moderately Resistant |

0.2 |

Note: * Data obtained from MASC 2024 Variety Market Share Report. ** Data obtained from the 2023 MCVET Winter Wheat and Fall Rye report. Fusarium Head Blight; FHB.

AAC Wildfire was the top seeded winter wheat variety, occupying 52.8 per cent of seeded winter wheat acres. This is an increase of just over nine per cent from 2023. AAC Wildfire was registered in 2015 and is a late maturing CWRW variety. AAC Vortex, which was registered in 2021, was seeded on just under nine per cent of acres in 2024, up close to five per cent from 2023. AAC Goldrush, which was registered in 2016, decreased in percentage of acres seeded, dipping by just under five per cent from 2023. AAC Overdrive, which was registered in 2022, increased in acres seeded by 0.2 per cent in 2024.

Emerson, which has a Fusarium head blight rating of “resistant,” has been the most seeded variety in Manitoba for several years. However, its acreage has dropped just over 20 per cent since 2022. A similar trend was seen in AAC Gateway, which dropped from 16.1 per cent in 2022, to just over five per cent in 2024. AAC Elevate, which had steady acreage of just over five per cent in 2022 and 2023, dropped out of the top eight in 2024.

Seed Manitoba Variety Selection and Growers Source Guide should be consulted when making variety selections.

By Jonothan Hodson

By Jonothan Hodson