Research on the Farm – Looking at the Effect of Plant Growth Regulators on Spring Wheat

Lodging is a major production issue in cereal crops. Cereals are especially prone to lodging in high-yielding environments. The greatest losses tend to occur 10 days to two weeks after head emergence. Plant growth regulators (PGRs) are a management tool available to reduce lodging in certain circumstances. PGRs are synthetic compounds that alter hormonal activity in the plant to modify plant growth and development, and are typically used to improve standability as they produce shorter, thicker stems. When are they warranted?

According to Anne Kirk, Cereal Specialist with Manitoba Agriculture and Resource Development, a PGR is most likely to be beneficial when you are growing a variety that is prone to lodging, using intensive management practices, and have high yield potential. “If a farmer is using a variety that might be prone to lodging and using a high nitrogen rate that will increase the plant growth, there is an increased risk of lodging and a farmer may want to consider using a PGR,” says Kirk.

Certain varieties respond more to PGR applications than others as PGR response is very variety specific. Conditions have to be really good for plant growth to consider using a PGR. Have growing conditions been really favourable? Does the wheat or other crop have really good yield potential? Environmental conditions leading up to PGR timing and the crops growth and yield potential could warrant it, especially if it’s a variety prone to lodging. On the other hand, if a plant is under any stress such as waterlogging, drought, nutrient deficiency, frost, insect or disease damage, a PGR should not be used. Since the plant is already under stress, applying a PGR could cause unintended consequences.

There are two main types of PGRs registered for use on spring and winter wheat, oats and barley in Western Canada – Manipulator and Moddus. The active ingredient in Manipulator is chlormequat chloride and the active ingredient in Moddus is Trinexapac-ethyl. Although the two have different active ingredients, their application timing and the crops they are registered for use on are quite similar.

“I think farmers would like to apply a PGR as a tank mix (with herbicides or fungicides), but the ideal timing for application is between herbicide timing and fungicide timing,” adds Kirk. “Herbicide timing is too early because the nodes haven’t emerged above the soil surface, and fungicide timing is too late (if targeting flag leaf timing for fungicide) because those nodes have already elongated. Applying a PGR isn’t going to shorten the plant at that point, it would just prevent future growth.”

Through the Research on the Farm program, Manitoba Crop Alliance (MCA) has been testing the efficacy of Manipulator since 2016, and is adding Moddus to the program in 2021. The objective of the Research on the Farm trial is to quantify the agronomic and economic impacts of using a PGR on plant height, lodging, yield and quality of wheat.

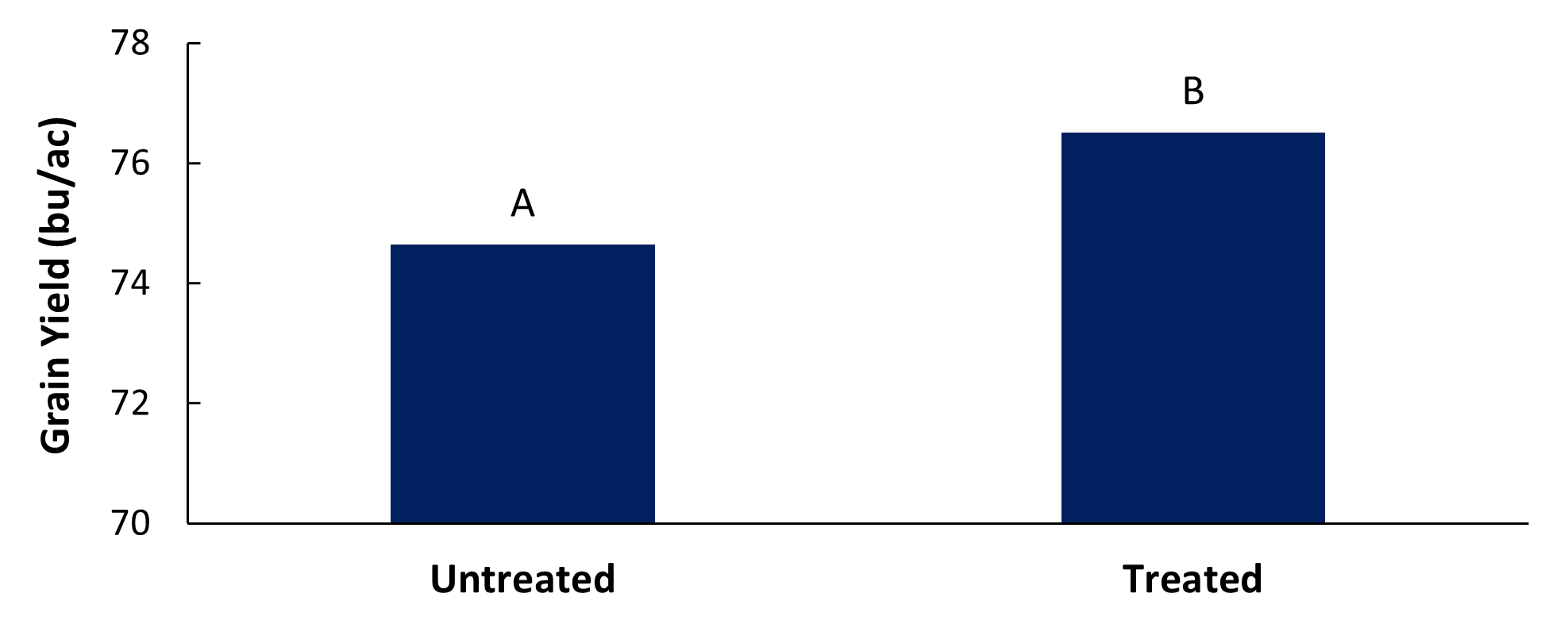

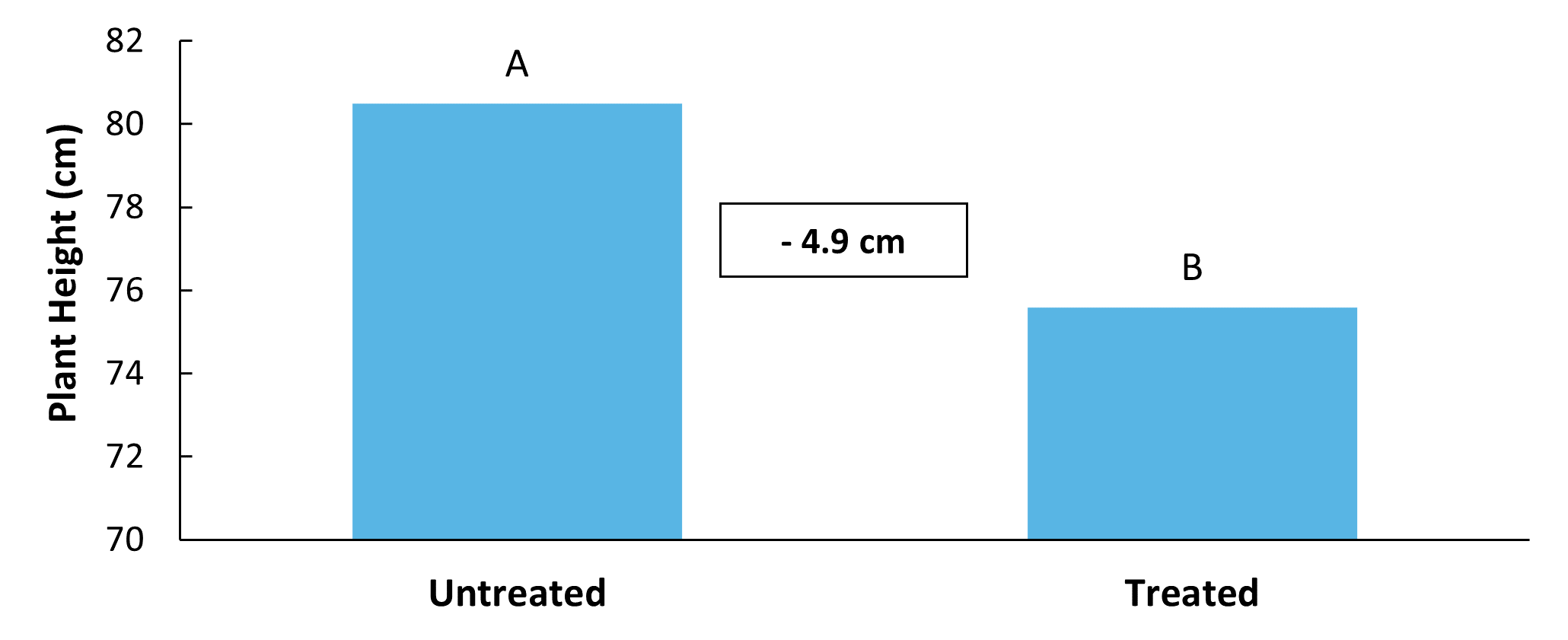

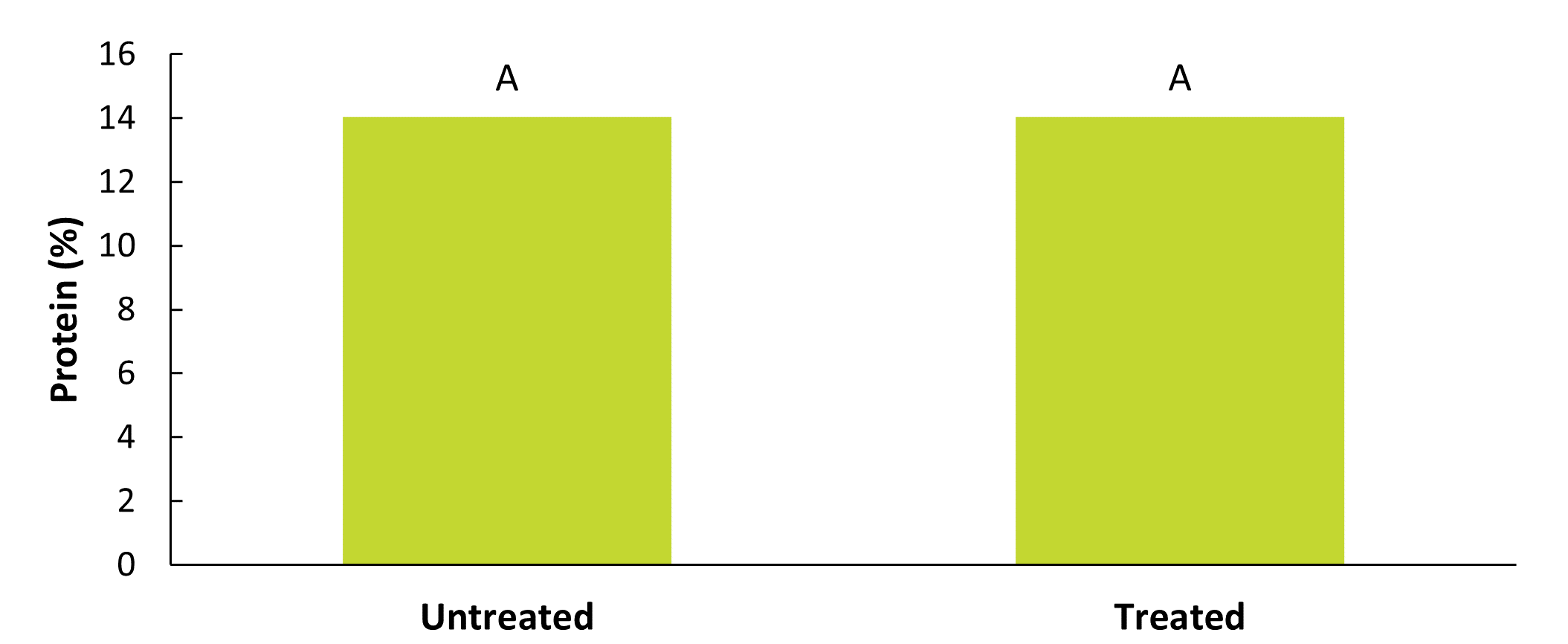

The PGR trial has run for three growing seasons (2018-2020) at a total of 32 sites. Three indicators were measured to get an idea of how the PGR application performed compared to the untreated check strips, grain yield (bu/ac), plant height (cm) and grain protein (percent). A small but significant effect was observed on grain yield, where a PGR application resulted in an average increase of 1.9 bu/ac. Similarly, plant height was also significantly impacted, where treated strips were on average 4.9 cm shorter than untreated check strips. Average grain protein across all site-years was 14.0%, for both treated and untreated strips, and no significant differences were observed. All three growing seasons (2018-2020) were relatively dry. Ideally, MCA would like to see data from a year with more moisture.

Figure 1. Average grain yield across all site-years (2018-2020) was 74.6 bu/ac for untreated strips and 76.5 bu/ac for strips treated with a PGR, resulting in a statistically significant yield increase of 1.9 bu/ac (P<0.05).

Figure 2. Average plant height across all site-years was 80.5 cm for untreated strips and 75.6 cm for strips treated with a PGR, resulting in a significant height reduction of 4.9 cm (P<0.05).

Figure 3. Average protein content was 14.0% for both untreated and treated strips across all site-years. No significant effect on grain protein content was observed in these trials.

Amy Mangin, a Ph.D. student at the University of Manitoba, is looking at PGR use in spring wheat as part of her research project. The project investigates PGRs and their interactions with different spring wheat varieties, nitrogen management strategies and planting densities. It also compares yield, protein and nitrogen use efficiency of spring wheat with and without PGRs.

“We’re looking at lodging as a whole aspect. Measuring things like stem strength, rooting plate, internode lengths and stem diameter,” says Mangin. “We’re using more detailed measurements to quantify how the PGRs are affecting the risk of lodging.”

PGRs reduce lodging typically through decreasing the canopy height as well as increasing stem strength. “We had a higher decrease in lodging when higher rates of nitrogen were applied as well as when high seeding rates were used,” says Mangin. “We really saw the benefit of the PGR when we were pushing yields with high N rates and high seeding rates.”

The objective of the three-year project is to better understand how high yielding spring wheat varieties respond to management practices such as nitrogen management, PGR application and seeding rate as well as their interactions and how these may influence lodging risk, yield and protein in Manitoba growing conditions.

For more information, please visit Agronomic Practices to Minimize Lodging Risk while Maintaining Yield Potential in Spring Wheat

Research on the Farm – Fungicide Management of Fusarium Head Blight

Article originally published in MCA’s spring 2021 version of The Fence Post newsletter.

Manitoba farmers are too familiar with the devastating toll Fusarium head blight (FHB) can cause in cereal crops. FHB is a serious disease that reduces yields and produces mycotoxins that impact human and animal health. Historically many farmers in high-risk FHB areas have applied a fungicide without questioning it.

Through the On-Farm Research Program, Manitoba Crop Alliance (MCA) is collecting data from real, working farms in order to give farmers more timely information and resources to help them fight this disease.

The Fungicide Timing for Management of FHB in Spring Wheat trials are in their fourth year. The objective of these trials is to provide further insight on the impact of fungicide application and timing on FHB disease levels in-season and in harvested grain.

This trial has run for three growing seasons at a total of 18 sites. A statistically significant effect on yield from fungicide application has only been observed in six out of 18 sites. Even when a significant effect on yield was observed, mycotoxin levels (DON) were very low. All three growing seasons have been relatively dry, which could explain the lack of DON accumulation. Ideally, we’d like to get some data on this from a wet growing season, where conditions favor FHB infection.

Colin Penner, a farmer from Elm Creek has participated in a number of On-Farm Research Trials over the years and sees the value on his farm.

“We’re in the Red River Valley so we spray for FHB on our farm,” says Penner. “The last number of years have been really dry so I’ve always questioned the effectiveness of fungicides, especially at head timing.”

Penner participated in the 2020 Fungicide Management of FHB in Spring Wheat trial and described it as a very simple process which produced surprising results on his farm.

“They came to the field and gave me the replication instructions which were straightforward and easy to follow. In this particular trial the results really surprised me. We’ve seen fungicides show a marginal benefit on dry years but I really didn’t expect to see the results we did by spraying late (not something I would aim to do). In our trials, to spray early was good and to spray late was even better.”

In Penner’s trial, the recommended application date was July 6 and the late timing strips were sprayed four days later, on July 10. At this site there was a statistical yield difference between the late timing strip and the untreated check, but there was no statistically significant yield difference between the recommended application timing and the untreated check.

Penner stressed the importance of randomized replicated trials to be able to compare the results with the information received from different companies. “I see a lot of data from companies that’s often not replicated. I think it’s important we do our own replicated trials like these ones. It adds value on my farm because it gets me thinking, and it’s also an opportunity to try different ideas and see what works well in my area.”

Tools like Manitoba Agriculture’s FHB risk maps (Link to: https://www.gov.mb.ca/agriculture/crops/seasonal-reports/fusarium-head-blight-report.html) combined with proper timing of fungicide application can help farmers reduce FHB risk.

“Manitoba Agriculture posts FHB Risk Maps daily (during the wheat flowering period) on our website. We also have a seven-day animation which shows the risks building or declining up to the point where you’re concerned about the crop,” says David Kaminski, Field Crop Pathologist, with Manitoba Agriculture and Resource Development.

“FHB is a difficult disease to work with; infection risk varies field to field. It depends on your seeding date. Some crops will escape just because, when they were flowering, infection-conducive conditions were not there in your specific area. Whereas a crop that was seeded a little bit earlier or a little bit later just hits it wrong and that’s when you’ll see disease.”

Kaminski says fungicide spraying needs to be very precise on the timing of crop development. “The heads have just come out and its prior to flowering. Depending on how much heat you are getting at the time, the application window can be as short as two days or as long as five days. It’s a tricky thing to determine,” adds Kaminski.

At the University of Manitoba (U of M) Dr. Paul Bullock, Professor, Dr. Manasah Mkhabela, Research Associate and Adjunct Professor, and Mr. Taurai Matengu, M.Sc. Student, Department of Soil Science, U of M are in year three of a five-year research project with an objective to better understand how weather relates to FHB risk levels in cereal crops.

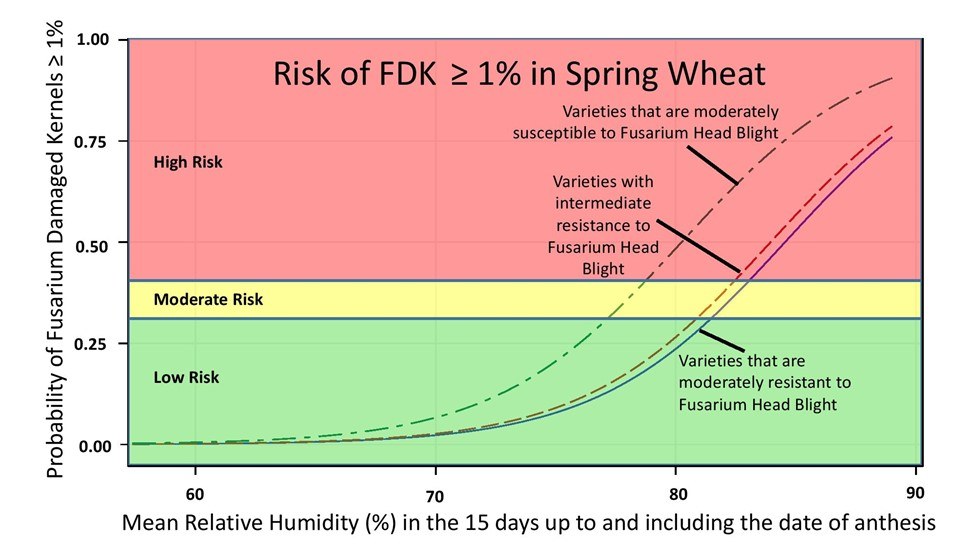

“If I’m a farmer and I’m going to apply a fungicide, there’s a cost to that application. So, the question is, is it worth it? What we’re trying to achieve through the FHB Risk Model is to give producers a model that when they monitor the weather in their fields, the model can calculate if the FHB risk is high, moderate, or low to help them with that decision,” says Bullock.

As more data is collected throughout the years of study, the models are updated and improved for accuracy. More farmers from across the prairies are getting involved which allows the data collected from their fields to be used to independently test the accuracy of the FHB risk models. Some of the research MCA is collecting from producers’ fields through the On-Farm Research Program will eventually be used to validate the accuracy of the models as well. The next phase of the project is to build an online platform using the model to provide FHB risk assessments across the prairies for producers.

The figure below is an example of how the model can be used to map out the risk levels based on different factors. This example shows how the probability of FDK risk level changes based on the average relative humidity in the 15 days leading up to an including the date of flowering.

Photo credit: Dr. Paul Bullock, Professor, Dr. Manasah Mkhabela, Research Associate and Adjunct Professor, and Mr. Taurai Matengu, M.Sc. Student, Department of Soil Science, U of M