MOISTURE TESTING SUNFLOWER SEED >15% MOISTURE

The following procedure is suggested for testing the moisture content of high moisture sunflower with the microwave oven.

- Harvest seed samples from different parts of the field and mix all samples together. Separate this total sample into at least four 50 gram samples for the tests. Make sure the samples are clean and hand pick out foreign material if necessary.

- Weigh a paper towel using a gram scale and record the weight. With the towel on the scale, pour a sample of seeds onto the scale and record that weight.

- Place the towel and seeds into the microwave oven; spread the seeds on the towel to a thickness of no more than about two seeds.

- Microwave for four-minute intervals; take out the sample and weigh it after each period. When the difference in weights become small, start weighing at two-minute intervals until there is no weight change. Lack of weight change indicates that the moisture has been removed.

- If running repeated samples for a long time, check to see if the glass tray in the oven is getting hot. If so, let the tray cool before running another test. If a sample starts to smoke or appears charred after a test, discard this sample and start another test after the oven and tray cool.

- Calculate the original seed moisture content of the sample by using the following equation. Be sure to subtract the weight of the paper towel from the initial and final sample weights before you begin the calculations.

Moisture content = (Initial weight – Final weight) / (Initial weight) x 100.

- Be sure to run a minimum of four tests and average the results.

- Do not leave the microwave oven unattended during the tests.

Confection sunflower should be under 10% moisture (between 9% and 10% is best) for proper storage. Oil sunflower moisture content should be 10% or less for winter storage and 8% or less for storage during warmer months.

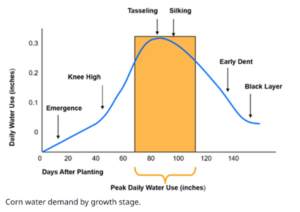

Getting there can be a balancing act at harvest: Wait too long for natural dry down, and sunflower standing in the field can become too dry and vulnerable to quality deterioration and shelling out. Cut too early and there’s greater chance for deterioration during storage if seed moisture is too high. Many experts advise combining ‘flowers at 12-15% moisture and using natural air drying to get stored see moisture under 10%.

HARVESTING HIGH MOISTURE SUNFLOWERS

Sunflowers can be combined when the seed moisture is below 20 percent. Harvesting when seed moisture is greater than 20 percent can result in scuffing during harvesting and shrinkage during drying. It would be preferable to combine seeds at 10 to 13 percent moisture.

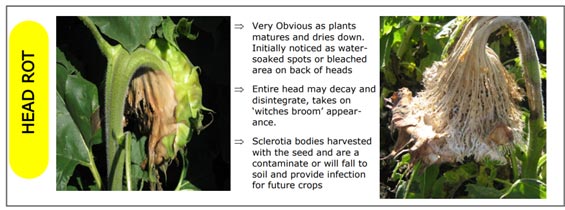

Scuffing is caused when sunflowers are harvested at a high moisture content. The combine causes mechanical damage by peeling away part or all of the top layer of the shell, giving the seed the appearance of sclerotinia damage or white seeds. Processors are known to discount for scuffing, even though it leaves no impact on the product itself.

Combine headers: Platform (wheat), row-crop, and corn headers have all been used successfully with sunflower. Row-crop heads are perhaps the best choice because they can be used without modification. Corn heads need to be modified with a stationary cutting knife before use with sunflower. Combines used for threshing small grains can be adapted to harvest sunflower with a variety of header attachments available with many operating on a head stripper principle.

Have the header platform raised high enough to take in the heads, minimizing stalks as much as possible. The overall goal of the threshing process should be passing the head nearly intact through the combine, or in a few large pieces, with all developed seed removed from the head. If the head is being ground up into small pieces, there will be excessive trash in the grain. Platform heads can be used without modification, but often have a higher amount of seed and head loss than a row head. Adding pans to the front of the platform, and/or modifying the reel can improve efficiency. Twelve-inch pans are best for 30-inch row spacings; 9-inch better for other row sizes and solid seeding.

Common threshing mistake: Waiting to harvest and seeds become too dry and shell out. Better: combine at 14-15% moisture and use air/dry down to under 10% moisture. Waiting too long to harvest can result in excessive field losses.

Threshing goal: Have the header platform raised high enough to take in the heads, minimizing stalks as much as possible. The overall goal of the threshing process should be passing the head nearly intact through the combine, or in a few large pieces, with all developed seed removed from the head. If the head is being ground up into small pieces, there will be excessive trash in the grain.

Fan speed: Air speed should be lower, due to the lighter weight of sunflowers (oils weigh about 28 to 32 lbs/bu, confection 22 to 26 lbs/bu). Excessive wind may blow seed over the chaffer and sieve, and seed forced over the sieve and into the tailings auger will be returned to the cylinder and may be dehulled. Set the fan so only enough air flow is created to keep trash floating across the screen/sieve. The concave should generally be run wide open (on a rotary combine, a rotor-to-concave setting of 3/4 to 1 inch is appropriate). A bottom screen or lower sieve of 3/8 inch, and a top screen/upper sieve of 1/2 to 5/8 inch is typical.

Forward speed: Combine forward speed should usually average between 3 and 5 miles per hour. Forward speed should be decreased as moisture content of the seed decreases to reduce shatter loss as heads feed into the combine. Faster forward speeds are possible with seed moisture between 12 and 15%.

Cylinder/rotor speed: Slow cylinder/rotor speed to 250 to 400 rpm. Normal cylinder speed should be almost 300 rpm (for a combine with a 22” diameter cylinder to give a cylinder bar travel speed of 1,725 feet per minute). Speed will vary depending upon crop conditions and combine used. Combines with smaller cylinders will require a faster speed and combines with a larger cylinder diameter will require a slower speed. A rotary combine with a 30”cylinder will need to be operated at 220 rpm, and a combine with a 17” cylinder will need to be operated at 390 to have a cylinder bar speed of 1,725 feet per minute. If a combine cylinder operates at speeds of 400 to 500 rpm, giving a cylinder bar speed of over 2,500 feet per minute, very little seed should be cracked or broken if the moisture content of the seed is above 11%. Cylinder bar speeds of over 3,000 feet per minute should not be used because they will cause excessive broken seed and increased dockage.

Concave clearance: When crop moisture is at 10% or less, conventional machines should be set open to give a cylinder to concave spacing of about 1″ at the front of the cylinder and about 0.75″ at the rear. A smaller concave clearance should be used only if some seed is left in the heads after passing through the cylinder. If seed moisture exceeds 15 to 20%, a higher cylinder speed and a closer concave setting may be necessary, even though foreign material in the seed may increase. Seed breakage and dehulling may be a problem with close concave settings. Make initial adjustments as recommended in the operator’s manual. Final adjustments should be made based on crop conditions.

Harvest Loss Rule of Thumb: Ten seeds per square foot (don’t forget heads that have seed left in them) represent a loss of 100 pounds per acre, assuming seed loss is uniform over the entire field. Harvest without some seed loss is almost impossible. Usually, a permissible loss is about 3%. Loss as high as 15 to 20% has occurred with a well-adjusted combine if the ground speed is too fast, resulting in machine overload.

Are your bins ready? Bins with perforated floors work better for drying sunflower than those with ducts. Aeration is essential, especially in larger bins. Aeration may be accomplished with floor-mounted ducts or portable aerators. Aeration fans should deliver 1/10 to 1 cfm per cwt of sunflower. If aeration is not available, sunflower should be rotated between bins to avoid hot spots developing in the stored grain.

Cleaning before storage: When excessive trash is present in the harvested grain, cleaning before storage can greatly reduce incidence of storage problems. Ambient air can be used to cool and dry sunflower. If heated air is used, generally a 10 degree F increase in temperature over ambient is sufficient to increase rate of drying. Be aware that sunflower dries more rapidly than corn or soybeans, and should be monitored to avoid over-drying.

Watch for Moisture Rebound: When tracking moisture readings on sunflower seeds that are being dried in a bun, keep in mind that the hull dries faster than the kernel. Thus, a moisture reading taken on sunflower being dried may be artificially low; for example, a moisture meter may give a reading of 10%, and then climb back up to 12% the next day. To get a more accurate reading, place some seed in a covered jar overnight and take moisture readings the next day, after the hull and kernel moisture have equalized.

Prepare for Fire Hazards: Always keep in mind that sunflower is an oil-based crop and fine fibers from sunflower seeds pose a constant fire hazard, especially when conditions are dry. Keep your combine and grain dryer free of chaff and dust (consider having a portable leaf blower on hand for this). Keep a small pressure sprayer or container filled with water on hand in the combine in case of fire. Should the threat of extreme dry conditions and combine fires persists; try nighttime harvesting when humidity levels are higher.

Lygus bugs can damage 30 to 35 seeds per head per adult. With the industry standard allowing for a maximum of 0.5 per cent kernel brown spot, the economic threshold for lygus bugs on sunflowers is about one lygus bug per nine heads. In research trials, damage to sunflower heads was approximately twice as severe when infestations occurred at late bud and early bloom compared to stages when heads had completed flowering. Thus, lygus bug management should be initiated prior to or at the beginning of the bloom stage if adult densities approach the economic threshold. Also, fields should be monitored for lygus bugs until flowering is complete to reduce incidence of kernel brown spot damage to confection sunflowers.

Lygus bugs can damage 30 to 35 seeds per head per adult. With the industry standard allowing for a maximum of 0.5 per cent kernel brown spot, the economic threshold for lygus bugs on sunflowers is about one lygus bug per nine heads. In research trials, damage to sunflower heads was approximately twice as severe when infestations occurred at late bud and early bloom compared to stages when heads had completed flowering. Thus, lygus bug management should be initiated prior to or at the beginning of the bloom stage if adult densities approach the economic threshold. Also, fields should be monitored for lygus bugs until flowering is complete to reduce incidence of kernel brown spot damage to confection sunflowers.