Effects of Drought Stress on Corn

The Prairies’ forecast for summer 2025 appears to be hot and dry. We know this is not ideal for corn growth, especially reproductive growth.

In recent years, we have dealt with drought stress in corn a lot. Fortunately, it has been overcome by timely rains and not had an impact province-wide. 2025 outlook is still unclear, but the heat doesn’t appear to be letting up and reproductive stages of corn are just around the corner.

So, what happens to the plant when there isn’t enough moisture? Most visibly, corn leaves begin to curl and make the plant resemble pineapple leaves or onion greens. This occurs because the leaves are protecting themselves from excessive moisture loss or transpiration. Believe it or not, the more readily a plant curls its leaves up, the more beneficial it is to that plant. This transpiration increases as leaf area increases and it is the mechanism that water moves from the soil, through the plant and into the atmosphere. If leaf rolling is resulting from true drought stress and occurs for 12+ hours a day, grain yield is likely to decrease, even prior to reproductive staging.

Come July, the crop will be at a detrimental stage for water requirements. At the end of June to the beginning of July, corn is growing vegetatively extremely quickly. By July 10 – 15, “normal” staging could be tasseling (VT) or silking (R1), but that varies, depending on emergence and environment. Both of these stages have a very high demand for soil moisture to support development.

“Potential ear size is already determined by the time silks emerge from the ear shoots. In fact, potential kernel row number is set by the 12-leaf collar stage (about chest-high corn.) Potential kernel number per row is determined over a longer time period, from about the 12-leaf collar stage to about 1 week prior to silk emergence” (https://www.agry.purdue.edu/ext/corn/pubs/corn-07.htm).

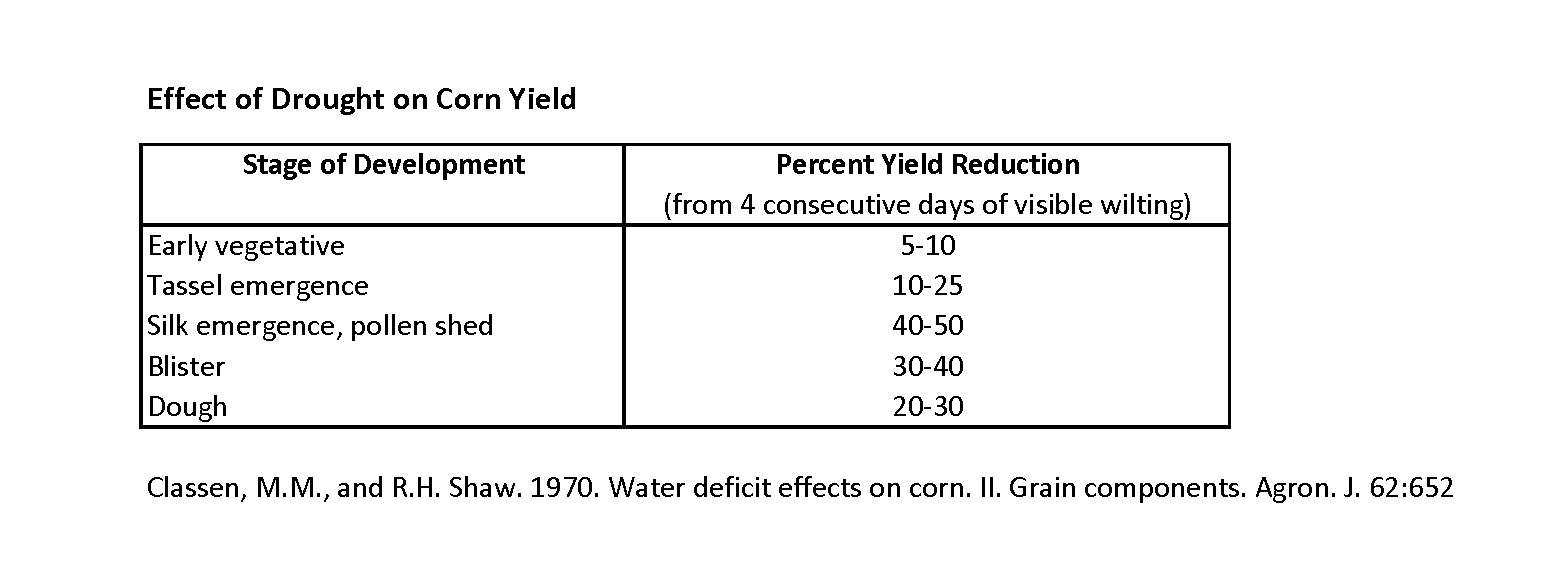

We know that row number is heavily predetermined through genetics, but kernels per row is not and has a strong sensitivity to environmental stresses. Below is a table identifying the potential yield reduction from drought stresses (with 4 consecutive days of leaf wilting) throughout the growing season.

Severe drought stress has the greatest impact during silk elongation, which often results in poor pollination. Silks on the base of the ear begin to elongate first, followed by those from the center and then the tip of the ear. So, when plant water is in low supply, the silks elongate slowly and may not even elongate beyond the husk. If the silk isn’t outside the husk during pollen shed, it will not pollinate those potential kernels. During these conditions, silks that do emerge have an increased chance of desiccating quickly, making them unable to receive pollen.

There is no gain made in worrying about what may happen over the next several weeks. What is promising is that corn has an amazing ability to recover from drought stress when it does receive rain. It is very unlikely that no pollination will occur whatsoever, but if dry conditions persist, it is likely that grain will not fill to its full potential. This is where rain events can really improve grain quality and the length of the crop’s life after it has been under severe stress.

Farming through a severe drought is something Manitobans haven’t had to do in decades and it is a steep learning curve. From excess winds to extreme heat to wildfires, all in May, there have been some stresses to endure already this season. Let’s hope for timely rains and a durable crop this year!