Research on the Farm – Fungicide Management of Fusarium Head Blight

Article originally published in MCA’s spring 2021 version of The Fence Post newsletter.

Manitoba farmers are too familiar with the devastating toll Fusarium head blight (FHB) can cause in cereal crops. FHB is a serious disease that reduces yields and produces mycotoxins that impact human and animal health. Historically many farmers in high-risk FHB areas have applied a fungicide without questioning it.

Through the On-Farm Research Program, Manitoba Crop Alliance (MCA) is collecting data from real, working farms in order to give farmers more timely information and resources to help them fight this disease.

The Fungicide Timing for Management of FHB in Spring Wheat trials are in their fourth year. The objective of these trials is to provide further insight on the impact of fungicide application and timing on FHB disease levels in-season and in harvested grain.

This trial has run for three growing seasons at a total of 18 sites. A statistically significant effect on yield from fungicide application has only been observed in six out of 18 sites. Even when a significant effect on yield was observed, mycotoxin levels (DON) were very low. All three growing seasons have been relatively dry, which could explain the lack of DON accumulation. Ideally, we’d like to get some data on this from a wet growing season, where conditions favor FHB infection.

Colin Penner, a farmer from Elm Creek has participated in a number of On-Farm Research Trials over the years and sees the value on his farm.

“We’re in the Red River Valley so we spray for FHB on our farm,” says Penner. “The last number of years have been really dry so I’ve always questioned the effectiveness of fungicides, especially at head timing.”

Penner participated in the 2020 Fungicide Management of FHB in Spring Wheat trial and described it as a very simple process which produced surprising results on his farm.

“They came to the field and gave me the replication instructions which were straightforward and easy to follow. In this particular trial the results really surprised me. We’ve seen fungicides show a marginal benefit on dry years but I really didn’t expect to see the results we did by spraying late (not something I would aim to do). In our trials, to spray early was good and to spray late was even better.”

In Penner’s trial, the recommended application date was July 6 and the late timing strips were sprayed four days later, on July 10. At this site there was a statistical yield difference between the late timing strip and the untreated check, but there was no statistically significant yield difference between the recommended application timing and the untreated check.

Penner stressed the importance of randomized replicated trials to be able to compare the results with the information received from different companies. “I see a lot of data from companies that’s often not replicated. I think it’s important we do our own replicated trials like these ones. It adds value on my farm because it gets me thinking, and it’s also an opportunity to try different ideas and see what works well in my area.”

Tools like Manitoba Agriculture’s FHB risk maps (Link to: https://www.gov.mb.ca/agriculture/crops/seasonal-reports/fusarium-head-blight-report.html) combined with proper timing of fungicide application can help farmers reduce FHB risk.

“Manitoba Agriculture posts FHB Risk Maps daily (during the wheat flowering period) on our website. We also have a seven-day animation which shows the risks building or declining up to the point where you’re concerned about the crop,” says David Kaminski, Field Crop Pathologist, with Manitoba Agriculture and Resource Development.

“FHB is a difficult disease to work with; infection risk varies field to field. It depends on your seeding date. Some crops will escape just because, when they were flowering, infection-conducive conditions were not there in your specific area. Whereas a crop that was seeded a little bit earlier or a little bit later just hits it wrong and that’s when you’ll see disease.”

Kaminski says fungicide spraying needs to be very precise on the timing of crop development. “The heads have just come out and its prior to flowering. Depending on how much heat you are getting at the time, the application window can be as short as two days or as long as five days. It’s a tricky thing to determine,” adds Kaminski.

At the University of Manitoba (U of M) Dr. Paul Bullock, Professor, Dr. Manasah Mkhabela, Research Associate and Adjunct Professor, and Mr. Taurai Matengu, M.Sc. Student, Department of Soil Science, U of M are in year three of a five-year research project with an objective to better understand how weather relates to FHB risk levels in cereal crops.

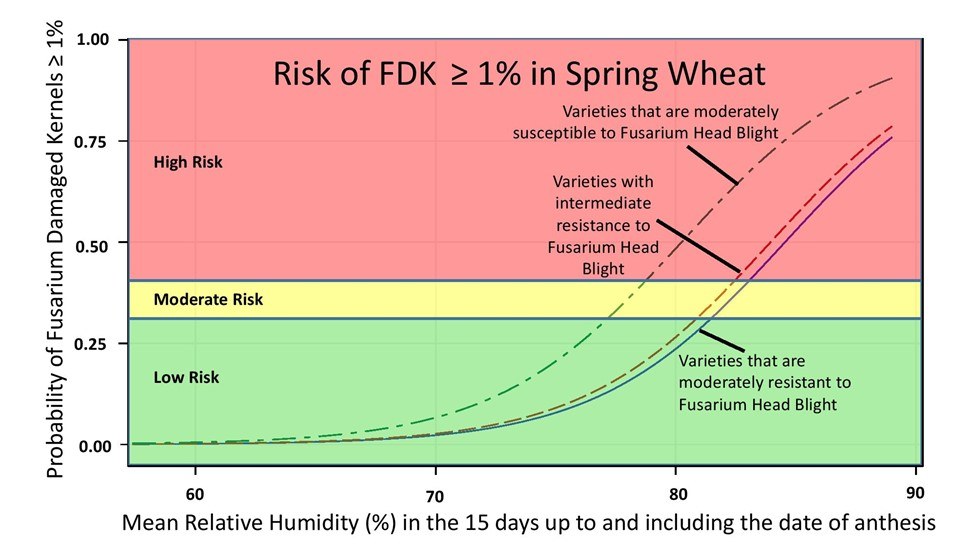

“If I’m a farmer and I’m going to apply a fungicide, there’s a cost to that application. So, the question is, is it worth it? What we’re trying to achieve through the FHB Risk Model is to give producers a model that when they monitor the weather in their fields, the model can calculate if the FHB risk is high, moderate, or low to help them with that decision,” says Bullock.

As more data is collected throughout the years of study, the models are updated and improved for accuracy. More farmers from across the prairies are getting involved which allows the data collected from their fields to be used to independently test the accuracy of the FHB risk models. Some of the research MCA is collecting from producers’ fields through the On-Farm Research Program will eventually be used to validate the accuracy of the models as well. The next phase of the project is to build an online platform using the model to provide FHB risk assessments across the prairies for producers.

The figure below is an example of how the model can be used to map out the risk levels based on different factors. This example shows how the probability of FDK risk level changes based on the average relative humidity in the 15 days leading up to an including the date of flowering.

Photo credit: Dr. Paul Bullock, Professor, Dr. Manasah Mkhabela, Research Associate and Adjunct Professor, and Mr. Taurai Matengu, M.Sc. Student, Department of Soil Science, U of M